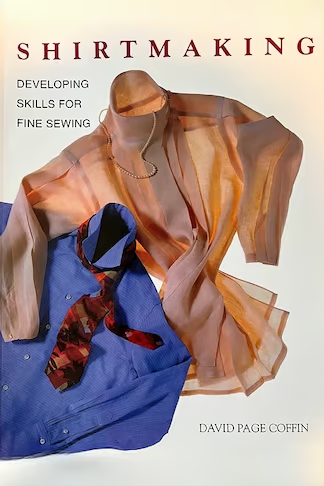

Shirtmaking: Developing Skills For Fine Sewing

- Author: David Page Coffin

- Published: 1993

- Format: paperback

- Started: 23 January 2025

- Finished: 15 February 2025

This is a must-read for any sewist who wants to up their shirtmaking game. It teaches you how to select materials, design a pattern to fit your body, and construct each part of the shirt, with lots of detailed explanations and diagrams.

The author strikes me as the Ken Forkish of sewing: a self-taught amateur goes on a mission to perfect his craft and writes an opinionated book on it. Or the other way around, since this was published two decades earlier.

Below are the notes I took while reading the book.

Introduction

Throughout my early days of shirtmaking, I felt certain that once I could make my own shirts, they would be better than the best I could buy because I could refine and experiment endlessly. p. vii

I’m writing for anyone who’s interested in shirtmaking, but my own involvement is that of an amateur: I’m on a challenging and satisfying quest for the best and most personal in shirts – or whatever I’m making – regardless of the time or reasonable expense. I make shirts for the sheer pleasure of the process, rather than as a time-saving or money-saving necessity. For instance, I have no interest in serging machines since, to me, they substitute an ugly seam done in a trice for a beautiful one that takes a little longer. Sergers may be great for many things, but, as far as I’m concerned, they spell cheap work in shirtmaking. p. ix

- A shirt from Turnbull & Asser, shirtmakers to King Charles III, cost well over $100 ready-to-wear, or $300 custom-made, minimum order four.1

Chapter 1: The Materials of Fine Shirts

- The best material for making shirts is cotton.

- Best types of cotton: Sea Island > Egyptian > Pima.

- Better cotton has longer individual fibers, called staples.

- Cotton is usually woven with 2-ply threads.

- Threads are numbered from 20 to 200 by size, where higher is finer.

- For example, “2×2 120” means both warp and weft are 2-ply 120 thread.

- Fine shirting cotton has a subtle and beautiful gloss/sheen, low fuzziness, and combines softness and crispness.

- Patterns are always woven in with yarn-dyed thread, not printed after.

- The names of classic shirting fabrics refer to different weaving effects.

- Poplin broadcloth: tightly woven, very high thread count, subtle variation on plain-weave, warp threads packed more densely than weft, slight shine.

- Lawn: less densely woven, summer-weight broadcloth.

- Voile: even less dense, almost transparent summer-weight broadcloth.

- Twill: parallel diagonal ribs, creating a pattern if woven in two colors.

- End-on-end: Multicolored variation of poplin broadcloth.

- Chambray: plain weave worked with two colors of yarns, usually a white warp and colored weft; comes in all weights.

- Oxford cloth: two-colored like chambray, but uses basketweave (warp and weft cross in pairs), giving it a soft bulkiness.

- You can also used silk, linen, and wool blends.

- Avoid polyester and poly-blend fabrics. They are not breathable.

- Woven, sewn-in interfacing is better than fusible (iron-on) interfacing.

- Plain bleached muslin (not permapress) works well as interfacing.

- Wash and dry your fabric before sewing to avoid shrinkage later on.

- “Dryers very gradually turn clothing into lint.”

- Before cutting fabric, iron it with the grain (parallel to the selvedge), stretching gently lengthwise but not crosswise.

Chapter 2: The Shirtmaker’s Tools

Essential tools for shirtmaking

- sewing machine

- felling foot & rolled-hem foot

- 2-ply cotton embroidery thread

- 60/8, 65/9, 70/10 machine needles

- fabric shears & short scissors

- tape measure & ruler

- pins & basting glue stick

- water soluble markers or chalk

- iron, ironing board, & spray bottle

- spray starch

- point presser & point turner

For pattern preparation and sewing practice

- woven cotton/polyester gingham for fitting

- scrap, all-cotton broadcloth

- bleached muslin for interfacing

- dark permanent marker

- heavy paper (poster board)

- dressmaker’s curve & tailor’s square

Desirable, but optional tools

- rotary cutter (Olfa)

- self-healing mat

- sleeve board

- walking foot

- button cutter

- buttonhole spacer

- magnetic pin holder

- corner radius template

Chapter 3: The Classic Shirt

- A classic shirt has one-piece pleated or gathered back; a narrow one- or two-piece double yoke; two front sections that overlap; flat felled armscye, side, and underarm seams; one-piece sleeves with plackets; either barrel or French cuffs; a collar on a separate stand; and a rolled hem.

- Author prefers a box pleat; hates locker loops and dislikes back darts.

The reason for back darts is purely cosmetic – to make the shirt follow or suggest an idealized shape, that is, the triangular back of the classically proportioned male. In the process, these darts turn a garment that’s traditionally loose-fitting and drapes smoothly into one that’s form-fitting and falls awkwardly on the body. p. 21

- A double yoke is vital, providing strength and concealing should seams.

- A narrower yoke is dressier (1 5/8ʺ to 2 1/2ʺ from front to back at shoulder), wider is sportier.

- You can make a split yoke to save material or make stripes parallel.

- Shirts traditionally close left over right for men, right over left for women.

- A front band is optional, and more American.

- Sleeve plackets need to be at least 1ʺ wide, and 7ʺ long if buttoned.

- Sleeves must be pleated or gathered to join the cuffs.

- Barrel cuffs are more common; French cuffs are closed with cufflinks.

- Collar should be topstitched at 1/4ʺ matching the cuffs.

- A pocket is not necessary. Author prefers without.

- Short stitches look better than long stitches, and give more stretch.

- Use at least 16 stitches per inch (1.6 mm), even up to 24 stitches per inch (1.1 mm). Use the same stitch length for construction and topstitching.2

- Use as short a stitch as possible for constructing parts turned inside out.

- For thread color, use an exact match or a slightly lighter color.

Chapter 4: Making Shirts Fit

- This book focuses on fitting shirts for men.

- The shirt evolved from a simple rectangular design to the modern shirt where almost all seams are shaped.

- The shoulder seam is the only definitive fit. The sleeves and torso are less fitted than a suite jacket for example, more loose flowing.

- There are ugly wrinkles when the yoke doesn’t match the shoulder slope.

- The yoke seams should rest just on the shoulder point. If in doubt, err towards narrow, especially for a slim figure.

- Too tight (buttoned) collars get forced up the neck, pulling the shirt away.

- Cuffs should fit the wearer’s wrist. Cuffs on RTW shirts are usually too big.

- Sleeves have a slight ease so that cuffs can stay put when extending arms.

- Sleeve width is a matter of opinion and traditionally fairly loose.

- The fit of the shirt body is based on comfort, fashion, and posture.

- Your posture (upright or slouched) greatly influences the fit of the shirt.

- Length depends on where you wear your waistband.

- You should be able to sit down and raise you arms straight above your head without pulling side seams out of trousers.

Comfort and fashion are often at odds with each other in many articles of clothing but should be reconciled in the traditional shirt. This shirt hangs smoothly and freely on the shoulders and over the chest, and then never again conforms tightly to the body. It hangs in a subtle balance between snugness and bagginess, and yet is neither. pp. 33–34

A well-fitted garment never calls attention to itself and never emphasizes but always conceals variations in the wearer’s body from the ideal. p. 34

- Yoke fit: Start with a yoke that fits across the shoulders.

- If the back is pleated, the yoke must be high enough so that tension in back is released in pleat rather than yoke.

- A rounded back to straight yoke effectively makes two horizontal darts, and should be positioned at the curve in the wearer’s back.

- Shoulder seam fit: Always adjust the shoulder seams of front and back to fit the yoke. Almost everyone needs shoulder slope adjustment.

- The author has four methods for making a custom shirt pattern.

Method #1: Adjusting a commercial pattern

- Typically make a muslin and then adjust whatever doesn’t fit.

- Measure a few significant places on an existing shirt so you know what pattern size to start with.

- There are lots of books on this; author doesn’t really like them.

Method #2: Drafting your own pattern

- Requires a draft, which is a set of instructions for a generic shirt which you plug measurements into.

- Gives similar results to a commercial pattern but is usually more basic.

- Author doesn’t really like these.

Method #3: Copying existing shirts

- You can copy and undarted, ungathered garment whose parts will lie flat.

- Need large sheets of paper. Try rolls of wrapping paper.

- Tape or pin paper over a thick folded towel, lay the garment down, anchor it, pin along seam lines, remove, and connect pinhole dots with pencil.

- You only need to trace half of all pieces, except the sleeves.

- It’s easier with a striped or plaid shirt so you can easily see the grain and be sure it’s not distorted.

- Straighten lines with a ruler and smooth out curves with a French curve.

- Check that all the seamlines fit together.

Method #4: Combined patternmaking method

- Author calls it the drape method.

- Copy yoke, armscye, and sleeve cap from an existing pattern or shirt.

- The best measurement to start with is yoke length (from shoulder to shoulder), but patterns often don’t list it. Chest measurement is next best.

- The next chapter goes over this method in more detail.

Chapter 5: Developing a Basic Pattern

- Almost no body is perfectly symmetrical, especially the shoulders.

- An asymmetrical pattern can fit better but it has pros and cons.

- Tools and materials: existing yoke pattern, 3 yd gingham or other fabric with visible grain, tight fitting T-shirt, sharp permanent markers, mirror, scissors, straightedge, French curve, and a friend to help.

Step 1: Prepare yoke

- Cut yoke with 5/8ʺ allowance (3/4ʺ for neckline) and mark center back.

- Press under all allowances except neckline (leave it flat).

Step 2: Position yoke

- Position test yoke at center back on model wearing a tight T-shirt.

- Smooth across shoulders, ignoring neckline. Clip allowance as necessary.

- Confirm you have too much material, not too little.

- Pin yoke in place and check neckline from the side.

Step 3: Prepare front

- Cut fabric long enough to go from neckline to hem plus 3ʺ, and wide enough to go around front of chest plus 4–5ʺ. Fold along CF and mark.

- Measure width of neck with fingers, transfer to ruler, and divide in half.

- Mark at one end of CF and reduce by 1/2ʺ (definitely smaller than neck).

- Draw a U-shaped neckline on fold and cut it, making a semicircle.

Step 4: Drape front

- Hold neckline to the model. Pin CF to T-shirt when bottom of U is snug against model’s neck in front. Pin CF at waistline.

- On one side, lift corner so grain is horizontal and lays over shoulder without letting it droop.

- Pin to middle of yoke until smooth from neck to armscye.

- Clip neckline allowance minimally, if necessary.

- Feel through to find front edge of yoke and mark it on front with dots.

- Repeat the process on other side.

Step 5: Establish front neckline

- Clip a bit more if necessary to make it lie flat.

- You want the snuggest fitting neck the model can stand.

- Draw ends of front neckline to blend smoothly into back neckline.

Step 6: Draping the back

- Cut another piece of fabric for the back. Mark CB.

- Pin to yoke CB with 1ʺ overlap. Pin at waist too.

- Don’t worry about pleats or gathers at this point.

- Lift corners and mark yoke edges. Mark an X at armscye ends.

- If model’s back extends further out below yoke bottom, darts will form; you can pin these in or make the yoke longer instead.

- If you slouch, the neckline might pull back; solve by taking a horizontal fold out of front chest 1/4ʺ to 3/4ʺ, and fix armscye which got smaller.

Step 7: Transfer armscye from pattern

- Label and unpin front and back.

- Align point on front where armscye and yoke cross with X made earlier.

- Pivot pattern until CF on both are parallel.

- Trace armscye seamline on test fabric.

- Repeat for both fronts and back.

- Draw vertical line from bottom of each armscye to hem.

- Smooth curves at yoke seamline on fronts and back with French curve.

- Trim yoke and armscye seams to create 1ʺ allowance.

- Trim side seams (unless waist is bigger than chest).

Step 8: Check progress and adjust side seams

- Unpin yoke and machine baste back and fronts to it RS together.

- Slit CF 6ʺ to fit over model’s head and pin it closed.

- Pin side seams at bottom of armscye and a few points down.

- You want shirt circumference to skim girth of body without diagonal wrinkles across side seams.

- Most likely problem with yoke is overfitting curves or shoulder slope.

- You can add ease to shoulder seam or make it flat instead of concave.

- Consider relaxing neckline by dropping up to 1/4ʺ in front.

- You can measure the collar stand with a 1ʺ wide strip pinned around first at CB, then along neckline, then crossing CF.

- Decide on the hem; usually longer in back than in front.

Step 9: Measuring sleeve length

- Measure from top of armscye seam to point where you want cuffs to end.

- Add 1ʺ for ease, then subtract cuff width.

More on sleeves

- Start with cuff you like, measure all around, then measure wearer’s wrist.

- Cuff should be wrist plus 1ʺ for ease plus 1ʺ for button overlap.

- Author likes lots of pleats, for example 5 of them taking in 3ʺ to 6ʺ total.

- Placket adds about 1ʺ to sleeve circumference.

- Sleeve cap and armscye should match, no need for easing.3

- Sleeve fit and appearance is usually controlled by changing the sleeve cap shape, not the armscye shape.

- If you simply traced the armscye, you’d have a convex sleeve cap. You would have to choose an angle (high and wide or low and narrow).

- Instead they’re usually concave at both ends, creating a built-in gusset.

- This compromise allows you to have a reasonably low angle while still having lots of reaching room because the gussets act like hinges.

- This extra fabric is why you can’t spread out a shirt flat.

- High sleeve angle: wide, pointing out, low cap (archer’s relaxed bow).

- Low sleeve angle: narrow, pointing down, high cap (archer’s drawn bow).

- Typical dress shirt has a 5ʺ cap, so fairly low angle and narrow.

Chapter 6: Collars, Plackets, Cuffs, and Pockets

Collars

- Shape of collar is a fashion issue that has little bearing on fit problems.

- Once you have a good collar stand, designing a collar to fit is simple.

- Adjust collar length by shortening or lengthening at CB.

- Collar stand is curved because neck is more like cone than cylinder.

- Collars and cuffs are the first part of a shirt that wears out.

Plackets, cuffs, and pockets

- A triangular fold at the top of the tower is classic.

- There is lots of leeway for placket width.

- You can even make it from two pieces to save fabric.

Chapter 7: A Workshop in Precision Sewing Techniques

Staystitching

- Staystitch all curved or bias seamlines using a 3 to 4 mm stitch length.

- In particular, staystitch the neckline and shoulder seams.4

- Use a very slightly smaller allowance so the main seam won’t be on top.

- Be careful to keep the fabric flat without stretching it.

- For curves, clip right up to the staystitching.

Straight seams

- Avoid ease (stretching one piece relative to the other).

- The feed dogs naturally stretch the top a bit more, depending on presser foot pressure and fabric slipperiness.

- A walking foot or integrated dual feed can help with that.

- Lightly stretch both layers by holding at each end and pulling evenly, without affecting the stitch length.

Curved seams

- To follow a curve, locate the center of a circle and pivot around it.

- Practice by sewing S-shaped scraps together.

- To sew curved to straight, straighten out the curved piece by clipping 1/4ʺ to 1ʺ apart, then pin together from the center working outward.

Eased seams

- Eased seams are where one edge is purposefully stretched.

- Fabric inside another piece must be smaller or it will buckle.

- Sewing a short piece eased to a long piece will pull the latter into a curve.

- Puller the shorter piece taut while sewing to ease it.

- This is done deliberately for collars, but it creates problems.

- Problem #1: Loose top collar. This is okay, you just need to iron carefully so that excess is hidden at back and disappears when worn.

- Problem #2: Seams pulled to underside of collar. This is actually a feature to conceal them, as long as it’s not too extreme.

- Problem #3: Change from original measured length. This just requires trial and error to get the desired collar length.

Construction ironing

- Completely different from normal ironing to make clothes look good.

- Normal ironing stretches the fabric while pressing does not.

- Spraying with water resets the stretch.

- Woven fabrics stretch more crosswise (weft) than lengthwise (wrap).

- Be careful not to stretch pieces when you’re only intending to crease.

- Author uses a separate spray bottle rather than steam in the iron.

Trimming seam allowances

- Grading straight allowances and clipping or removing curved and corner allowances: both reduce bulk.

- The widest layer of a graded allowance should face the outside.

- Grade for the yoke, straight parts of collar, collar stand, and cuffs.

- Instead of clipping wedges, better to use very small stitches and then cut off corner allowances completely.

Edgestitching and topstitching

- Holds seams and interfacing in place, also decorative.

- Edgestitching serves as construction for sleeve plackets and pockets.

- Edgestitch distance should be well under 1/16ʺ otherwise it’s topstitching.

- Adjust thread tension so that best looking stitch comes out on top.

Flat felled seams and rolled hems

- Should be done with special feet or not at all, unless 1/4ʺ or wider.5

- A hemmer foot folds twice while a feller foot folds once.

- Start to fold/roll by hand, then feed it into the foot.

- The feet have trouble with bulk, as in crossing the other flat felled seam, so you might need to skip that part and hand sew afterwards.

- There are many different hem styles; sharper curves are harder to make.

- Flat felled seams look equally nice on both sides, but be consistent.6

- Author is picky about mirroring flat felled seams so they’re symmetrical.

Sewing the sleeve/body seam

- It’s too big and curved for the felling foot.

- Solution: fold under the allowance before sewing.

- When folding over, start from each end and meet in middle.

- Pin midpoint together and sew from there to each end, doing a bit at a time and realigning to keep parallel. Then topstitch 3/8ʺ from first seam.

- No need to trim any allowances except at yoke ends.

Attaching cuffs and collar bands

- Clever trick to ensure ends of cuff match edge of plackets with little bulk.

Collar stand construction

- Usual approach is to attach collar to stand, then whole thing to shirt.

- Better to attach collar stand to shirt, then attach the collar.

Placket construction

- Placket goes towards back of sleeve, with tower close to center.

- When turning corners, if it looks like you’ll overshoot, decrease the stitch length with needle up.

Turning collar points

- Method #1: Stitch almost to point, then across; trim allowances almost all away right at point, then turn collar.

- Method #2 (Adriana Lucas): Follow stitching line exactly (sharp turn at corner), trim interfacing only, various folds.

Making the collar

- This is the hardest part of shirtmaking.

Chapter 8: Sewing It All Together

Seam allowances

- Commercial patterns are obsessed with using 5/8ʺ allowances everywhere.

- Better to use whatever seam allowances are best for construction.

- Yoke: neckline 1/4ʺ, front & back 5/8ʺ, shoulders 3/8ʺ (flat felled).

- Front & back: top (yoke) 5/8ʺ, armholes 3/8ʺ, side front 1/2ʺ and side back 1/4ʺ (assuming 1/4ʺ flat felling), bottom 1/4ʺ.

- CF: CF 3/4ʺ for overlap and 1 3/4ʺ for allowance (2 1/2ʺ total).

- Sleeves: armhole 7/8ʺ, underarm front 1/2ʺ and back 1/4ʺ, bottom 5/8ʺ.

- Plackets: 1/4ʺ.

- Cuffs: outer 1/4ʺ, sleeve seam 5/8ʺ.

- Collar stand: 1/4ʺ.

- Collar: collar stand end 5/8ʺ, rest 1/4ʺ.

Clipping

- Clip 1/8ʺ to mark these points: CF (fronts), CB (yoke, neckline, collar, collar stand), shoulder seams and placket spots (sleeves).

- Vertical stripes on grain on shirt body result in horizontal stripes on collar, yoke, and cuffs.

Pattern layout

- Can use different material for inner yoke, under collar (stand), under cuff.

- Or make a contrasting collar, cuff, or pocket.

- Curve hem more to have more scrap fabric left.

- Make sleeve plackets from two smaller scraps cut down center line.

- Can also make a sleeve out of two pieces.

Putting the shirt together

- Cut pieces, staystitch shoulder seams.

- Pleat back, optionally monogram inner yoke.

- Attach yokes to back with single seam; grade, press to yoke; fold inner back down; edgestitch outer yoke and all allowances.

- Construct fronts, pockets.

- Sew fronts to inner yoke WS together, with graded seams pressed to yoke; fold over top yoke; edgestitch it on top.7

- Staystitch around neckline.

- Attach collar stand.

- Try on shirt and pin front and collar stand at CF; mark where would want ends of collar to be at top edge of the stand, centering them carefully.

- Make sleeve plackets.

- Prepare sleeve caps for flat felling; attach sleeves.

- Flat fell side seams.

- Measure cuffs, make pleats, attach cuffs; make and attach collar.

- Make rolled hem.

- Try on and position buttonholes.

- Make buttonholes and attach buttons.

On buttons and buttonholes

- Trick is to cut open buttonhole without cutting stitches.

- Buttons and buttonholes should be 3/4ʺ from CF edge.

- Author does buttonholes with manual zigzag and bartack.

- Author sews buttons on by hand (using unwaxed dental floss!).

- Can also double/triple thread to sew on buttons faster.

- Men’s shirt usually has 6 to 7 buttons (including collar stand button).

- Cuffs can be buttoned at midpoint of edge or a little off it.

- Get buttons from thrift stores or from old/cheap shirts.

Ironing the shirt

- Iron least to most visible: back, yoke, sleeves, cuffs, collar, front.

- Use the square end of the ironing board.

Working with striped fabrics

- Easier to see grain line, but you also need to match up stripes.

Chapter 9: Variations on a Classic Theme

- rectangular shirt evolution

- vestigial gusset

- bib front

- continuous rolled hem

- CF band extension triangle

- overshirts, knit fabrics

- back expansion panel

- elbow patches

- silk lining

- covered-button plackets

- rugby shirt

- That was in 1985. In 2025, it’s more like $200 or $300 RTW and $600 custom. ↩︎

- This is really surprising to me! Everyone else seems to recommend 2.4 mm for construction and lengthening to 3 mm for topstitching ↩︎

- This advice is contrary to the standard practice (as I understand it) of easing a larger sleeve cap into a smaller armscye for better mobility. ↩︎

- You’d think this would include armholes too, but it seems most people don’t bother. ↩︎

- In 2015, David Page Coffin replied to a PatternReview thread saying 1/4ʺ flat felled seams are common and it’s perfectly fine to make them without special feet. ↩︎

- In my Fairfield Shirt I felled the armscye seams inside and the side seams outside, and I think it looks fine that way. ↩︎

- This differs from the burrito method, where you baste the fronts to the yoke and then sew the yoke, fronts, and yoke facing with one seam. ↩︎